Election polling errors blamed on 'unrepresentative' samples

- Follow the latest updates with BBC Politics Live

- Laura Kuenssberg: Why were the polls so wrong?

- David Cowling: Will pollsters redeem themselves in 2016?

The failure of pollsters to forecast the outcome of the general election was largely due to "unrepresentative" poll samples, an inquiry has found.

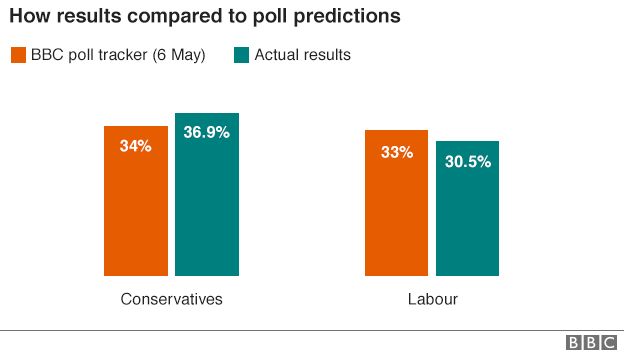

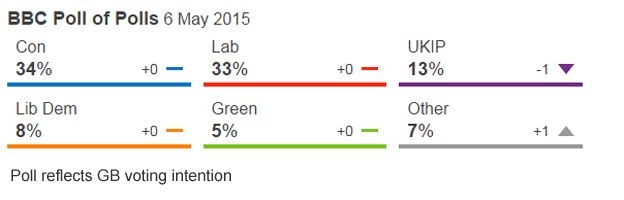

The polling industry came under fire for predicting a virtual dead heat when the Conservatives ultimately went on to outpoll Labour by 36.9% to 30.4%.

A panel of experts has concluded this was due to Tory voters being under-represented in phone and online polls.

But it said it was impossible to say whether "late swing" was also a factor.

The majority of polls taken during last year's five-week election campaign suggested that David Cameron's Conservatives and Ed Miliband's Labour were neck-and-neck.

This led to speculation that Labour could be the largest party in a hung parliament and could potentially have to rely on SNP support to govern.

But, as it turned out, the Conservatives secured an overall majority in May for the first time since 1992, winning 99 more seats than Labour, their margin of victory taking nearly all commentators by surprise.

'Statistical consensus'

The result prompted the polling industry to launch an independent inquiry into the accuracy of their research, the reasons for any inaccuracies and how polls were analysed and reported.

An interim report by the panel of academics and statisticians found that the way in which people were recruited to take part - asking about their likely voting intentions - had resulted in "systematic over-representation of Labour voters and under-representation of Conservative voters".

These oversights, it found, had resulted in a "statistical consensus".

How opinion polls work

AFP

AFP

Most general election opinion polls are either carried out over the phone or on the internet. They are not entirely random - the companies attempt to get a representative sample of the population, in age and gender, and the data is adjusted afterwards to try and iron out any bias, taking into account previous voting behaviour and other factors.

But they are finding it increasingly difficult to reach a broad enough range of people. It is not a question of size - bigger sample sizes are not necessarily more accurate.

YouGov, which pays a panel of thousands of online volunteers to complete surveys, admitted they did not have access to enough people in their seventies and older, who were more likely to vote Conservative. They have vowed to change their methods.

Telephone polls have good coverage of the population, but they suffer from low response rates - people refusing to take part in their surveys, which can lead to bias.

This, it said, was borne out by polls taken after the general election by the British Election Study and the British Social Attitudes Survey, which produced a much more accurate assessment of the Conservatives' lead over Labour.

NatCen, who conducted the British Social Attitudes Survey, has described making "repeated efforts" to contact those it had selected to interview - and among those most easily reached, Labour had a six-point lead.

However, among the harder-to-contact group, who took between three and six calls to track down, the Conservatives were 11 points ahead.

'Herding'

Evidence of a last-minute swing to the Conservatives was "inconsistent", the experts said, and if it did happen its effect was likely to have been modest.

Former Lib Dem leader Nick Clegg has suggested such a swing, ascribing it to voters' fears about a hung parliament and a possible Labour-SNP tie-up.

It also downplayed other potential explanations such as misreporting of voter turnout, problems with question wording or how overseas, postal or unregistered voters were treated in the polls.

However, the panel said it could not rule out the possibility of "herding" - where firms configured their polls in a way that caused them to deviate less than could have been expected from others given the sample sizes. But it stressed that did not imply malpractice on behalf of the firms concerned.

Prof Patrick Sturgis, director of the National Centre for Research Methods at the University of Southampton and chair of the panel, told the BBC: "They don't collect samples in the way the Office for National Statistics does by taking random samples and keeping knocking on doors until they have got enough people.

"What they do is get anyone they can and try and match them to the population... That approach is perfectly fine in many cases but sometimes it goes wrong."

Prof Sturgis said that sort of quota sampling was cheaper and quicker than the random sampling done by the likes of the ONS, but even if more money was spent - and all of the inquiry's recommendations were all implemented - polls would still never get it right every time.

Analysis by the BBC's political editor Laura Kuenssberg

EPA

EPA

I remember the audible gasp in the BBC's election studio when David Dimbleby read out the exit poll results.

But for all that the consequences of that startling result were many and various, the reasons appear remarkably simple.

Pollsters didn't ask enough of the right people how they planned to vote. Proportionately they asked too many likely Labour voters, and not enough likely Conservatives

Politics is not a precise science and predicting how people will vote will still be a worthwhile endeavour. Political parties, journalists, and the public of course would be foolish to ignore them. But the memories and embarrassment for the polling industry of 2015 will take time to fade.

Joe Twyman, from pollster YouGov, told the BBC it was becoming increasingly difficult to recruit people to take part in surveys - despite, in YouGov's case, paying them to do so - but all efforts would be made to recruit subjects in "a more targeted manner".

"So more young people people who are disengaged with politics, for example, and more older people. We do have them on the panel, but we need to work harder to make sure they're represented sufficiently because it's clear they weren't at the election," he said.

Pollsters criticised for their performance have pointed to the fact that they accurately predicted the stellar performance of the SNP in Scotland - which won 56 out of 59 seats - and the fact that the Lib Dems would get less than 10% of the vote and be overtaken by UKIP.

2015.5.17

我們靜待British Polling Council (BPC)專業分析報告。

Predicting the result

Pollderdash 看不懂標題。

Why the opinion polls went wrong

May 16th 2015 | From the print edition

IT WAS supposed to be the closest general election for several decades. At least ten final opinion polls put the Conservative and Labour parties within a percentage point of each other. Politicians were being told firmly that some kind of coalition government was inevitable. But all that turned out to be wrong. The Tories ended seven points ahead of Labour in the popular vote and won a majority in the House of Commons. Why were the projections wrong?

In 1992 pollsters made a similar error, putting Labour slightly ahead on the eve of an election that the Tories won by eight points. The often-cited explanation for this mistake is so-called “shy Tories”—blue voters who are ashamed to admit their allegiance to pollsters. In fact that was just one of several problems: another was that the census data used to make polling samples representative was out of date.

Following an inquiry, pollsters improved. A similar review has now been launched by the British Polling Council (BPC), but its conclusions may be less clear cut. In 1992 all the pollsters went wrong doing the same thing, says Joe Twyman of YouGov. This time they went wrong doing different things. Some firms contact people via telephone, others online, and they ask different questions. Statistical methods are hotly debated.

That has led to almost as many explanations for the error as there are polling firms. The “shy Tories” might have reappeared, but this cannot explain the whole picture. Ipsos MORI, for instance, only underestimated the Tory share of the vote by one percentage point—but it overestimated support for Labour. Bobby Duffy, the firm’s head of social research, says turnout might explain the miss. Respondents seemed unusually sure they would vote: 82% said they would definitely turn out. In the event only 66% of electors did so. The large shortfall may have hurt Labour more.

Others reckon there was a late swing to the Tories. Patrick Briône of Survation claims to have picked this up in a late poll which went unpublished, for fear that it was an outlier 異常值. Polls are often conducted over several days; Mr Briône says that slicing up the final published poll by day shows movement to the Tories, too. Yet this is contradicted by evidence from YouGov, which conducted a poll on election day itself and found no evidence of a Tory surge.

One firm, GQR, claims to have known all along that Labour was in trouble. The polls it conducted privately for the party consistently showed Labour trailing. Unlike most other pollsters, GQR “warms up” respondents by asking them about issues before their voting intention. Pollsters tend to be suspicious of so-called “priming” of voters, which seems just as likely to introduce bias as to correct it.

The BPC’s inquiry will weigh up the competing theories. Given the range of methods and the universal error, a late surge seems the most plausible explanation for now. That would vindicate Lynton Crosby, the Tory strategist, who insisted voters would turn blue late on. Next time expect more scepticism about polls—and more frantic last-minute campaigning.

IT WAS supposed to be the closest general election for several decades. At least ten final opinion polls put the Conservative and Labour parties within a percentage point of each other. Politicians were being told firmly that some kind of coalition government was inevitable. But all that turned out to be wrong. The Tories ended seven points ahead of Labour in the popular vote and won a majority in the House of Commons. Why were the projections wrong?

In 1992 pollsters made a similar error, putting Labour slightly ahead on the eve of an election that the Tories won by eight points. The often-cited explanation for this mistake is so-called “shy Tories”—blue voters who are ashamed to admit their allegiance to pollsters. In fact that was just one of several problems: another was that the census data used to make polling samples representative was out of date.

Following an inquiry, pollsters improved. A similar review has now been launched by the British Polling Council (BPC), but its conclusions may be less clear cut. In 1992 all the pollsters went wrong doing the same thing, says Joe Twyman of YouGov. This time they went wrong doing different things. Some firms contact people via telephone, others online, and they ask different questions. Statistical methods are hotly debated.

That has led to almost as many explanations for the error as there are polling firms. The “shy Tories” might have reappeared, but this cannot explain the whole picture. Ipsos MORI, for instance, only underestimated the Tory share of the vote by one percentage point—but it overestimated support for Labour. Bobby Duffy, the firm’s head of social research, says turnout might explain the miss. Respondents seemed unusually sure they would vote: 82% said they would definitely turn out. In the event only 66% of electors did so. The large shortfall may have hurt Labour more.

Others reckon there was a late swing to the Tories. Patrick Briône of Survation claims to have picked this up in a late poll which went unpublished, for fear that it was an outlier 異常值. Polls are often conducted over several days; Mr Briône says that slicing up the final published poll by day shows movement to the Tories, too. Yet this is contradicted by evidence from YouGov, which conducted a poll on election day itself and found no evidence of a Tory surge.

One firm, GQR, claims to have known all along that Labour was in trouble. The polls it conducted privately for the party consistently showed Labour trailing. Unlike most other pollsters, GQR “warms up” respondents by asking them about issues before their voting intention. Pollsters tend to be suspicious of so-called “priming” of voters, which seems just as likely to introduce bias as to correct it.

The BPC’s inquiry will weigh up the competing theories. Given the range of methods and the universal error, a late surge seems the most plausible explanation for now. That would vindicate Lynton Crosby, the Tory strategist, who insisted voters would turn blue late on. Next time expect more scepticism about polls—and more frantic last-minute campaigning.

沒有留言:

張貼留言