Green Creating Change above the Line – A Talk with Peter Senge

EDF’s Corporate Partnerships team was just treated to some mind-expanding thinking at our annual retreat, courtesy of Peter Senge. Peter is a senior lecturer at MIT, author of the widely-read systems-thinking book, The Fifth Discipline, founding Chairman of the Society for Organizational Learning, and recently the author of The Necessary Revolution, an in-depth study on how individuals and organizations can successfully work together to create a sustainable world.

Peter began by sharing the birth story of the Quality Management Revolution, fathered by W. Edwards Deming in the 1950s. Deming first successfully pushed his transformational ideas into Japan’s business culture, resulting in the implementation of Japanese quality programs that later were emulated by American car companies. And while these quality programs had an overall positive effect on car companies, in Deming’s mind these initiatives never led to fundamental change that could truly revolutionize future ways of thinking and operating. They never created change “above the line” – that is, truly fundamental change.

Our discussion with Peter was centered on a two by two matrix that simplifies a way to broadly assess companies’ sustainability efforts. Along the x-axis, efforts are scaled by the level of internal versus external control necessary to make that effort possible. Is the effort an internal one to the company or does it require cooperation from governments, other companies and/or associations? The y-axis rates the timescale of the effort. The upper quadrants imply long-term efforts and those that fall beneath the x-axis imply short term actions. A solution for a more long-term problem will fall higher on the y-axis in contrast to a quick-fix, which would drop below the x-axis.

Much of the work around business sustainability lies “below the line.” At EDF, we encourage companies to implement energy efficiency programs such as EDF Climate Corps; we work with KKR’s portfolio companies to measure and improve their energy use, waste and water; and we even push for an increase of the energy efficiency of Walmart’s factories in China. Peter pointed out that this work is critical: we have to start somewhere.

But we really need to focus our work above the line, as well. While below-the-line efforts build momentum and credibility to get us on the path to fundamental change, these efforts alone won’t enable us to achieve true sustainability. Peter talked about a few key things that can help, such as understanding the complete system in which the company functions, reflecting on our mental models and setting aspirational goals.

Also worth considering is whether we are working to achieve fundamental solutions to a problem or simply addressing the problem’s symptoms. Yes, taking an aspirin for your headache will alleviate the pain, but if the headache comes back each and every day, you’d better address the root cause. Yes, go ahead and implement energy efficiency in your company, but don’t forget that fundamental solutions are where your biggest leverage may be – creating a product that enables the smart grid, for example, or developing an entirely new business model that offers services (and overall much lower impacts) instead of products.

At the end of our session, I asked Peter whether he felt optimistic about the world’s environmental situation

He paused, smiled and then quoted Dee Hock, the founder and former CEO of Visa, who once said:

“It’s far too late for pessimism.” So, let cost and risk drive the first steps toward sustainability.

Generate momentum.

Learn.

And build that bridge to real sustainability by doing the hard work that will put your company above the line and on the path to fundamental change.

Thank you, Peter.

*****

Design Thinking June 11, 2008, 2:55PM EST text size: TT Peter Senge's Necessary Revolution

In a new book, the management guru discusses the environmental woes facing business and some steps that may lead to a more sustainable world

Peter Senge, a professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Sloan School of Management and founder of the Society for Organizational Learning, is perhaps best known for his 1990 best-selling book, The Fifth Discipline, which introduced the idea of the "learning organization." Now, Senge has a new work that promises to be as influential as the first. In The Necessary Revolution: How Individuals and Organizations Are Working Together to Create a Sustainable World (Doubleday, 2008), Senge and his co-authors grapple with the daunting environmental problems we face, and highlight innovative steps taken by individuals and corporations, often in partnership with global organizations such as Oxfam, toward a more sustainable world.

It may seem surprising that an expert in management and organizational change is focusing on sustainability, but there is a strong connection to Senge's work. In his earlier book, he laid out an approach to management that combines systems thinking, collaboration, and team learning. As he describes it, a learning organization is one in which "people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspiration is set free, and where people are continually learning to see the whole together." Such organizations tend to be more flexible, adaptive, and productive—critical qualities in a time of rapid change.

In The Necessary Revolution, Senge applies the same thinking to a system bigger and more complex than the organization: global society. The book is a call to arms, an argument to business leaders that they must rethink their approach to the environment or, as one executive told Senge, "we won't have businesses worth being in in 20 years." But the authors don't linger on the problems, focusing instead on the stories and insights of successful innovators, on creative solutions, and on practical approaches to meeting these challenges. Jessie Scanlon recently met Peter Senge at his Cambridge (Mass.) office to talk about the critical role that business will play in the coming revolution, the visionary leaders at companies such as Nike (NKE) and Costco (COST), and the future of the corporation. An edited version of their conversation follows.

Why did you title the book The Necessary Revolution?

I don't really like the word "necessary" because it makes it seem we have no choice. On the one hand, we don't. There's only so much water in the world. There's only so much topsoil. There's only one atmosphere, so there's only so much CO2 that can be stuffed into the atmosphere. But real change occurs when people make choices. We're not going to get out of the predicament that we're in by a lot of teeny incremental things. It's going to take bold ideas.

The word "revolution" was meant to be in the spirit of the Industrial Revolution. Not a political revolution because this absolutely has to be a nonpartisan issue. The future doesn't belong to one party or another.

In the book, you argue that we must shed "industrial age beliefs." Can you elaborate?

One industrial age belief is that GDP or GNP is a measure of progress. I don't care if you're the President of China or the U.S., if your country doesn't grow, you're in trouble.

But we all know that beyond a certain level of material need, further material acquisition doesn't make people happier. So you have a society predicated on the idea that you have to keep growing materially, and yet nobody actually believes it.

How dominant is the price-value model in business today? Has the success of products like the Toyota Prius convinced companies that consumers care about more than narrowly defined self-interest?

It's still dominant. Now, I don't think there's anything inherently wrong with price-value. [The problem is] the unquestioned assumptions about how we define it. At some point it becomes tautological. How do you know what people value? Well you watch what they buy. How do we know what products to create? Well, it's based on what they value.

We've done a lot of work with companies in Detroit, and when the Prius came out, I asked them what they thought of it. Everyone said the same thing: "It's a niche product." They said: "In focus groups, we ask people how much they would pay for a 10% improvement in fuel efficiency, and it's always a small number." But you're never going to learn latent demands from focus groups. Toyota (TM) didn't introduce the Prius because of a focus group. They were convinced that cars needed to change.

In The Necessary Revolution, you profile people, working independently or within companies or organizations, who are trying to bring about a more sustainable world. As you learned their stories, what patterns emerged?

The first is obvious: People have to be passionate. These are innovators in a fundamental sense, and innovators innovate because there is something that they are passionate about. Second, they all in different ways were able to step back and see a bigger picture. This is a huge challenge for people in companies, because so many companies are dominated by short-term perspective and because lots of people in key positions simply aren't very good or don't care very much about the bigger picture. Watch how the decisions are made. Are they thinking of the value of the company 10 years after they retire, or are they thinking about the value of their stock options this year?

The other two things we focused on are the ability to connect with lots of people and collaborate across boundaries—you could call it high levels of relational intelligence. The final element that we saw again and again is a shift [in strategy] away from "we've got to stop doing x, y, or z" and all the negativism that tends to pervade these issues.

Can you give some specific examples?

Nike is a great example of these last two qualities. The company's [eco-friendly Considered system] came into being because of two women who were consummate networkers and who realized that "we're never going to change this culture by convincing people that toxins are bad and that we should be less bad. What's going to make people really passionate is the idea that we can do something that no one has done before and that it will be a great thing for athletes." So they started talking to designers and getting them excited about different kinds of shoes. They created the Organic Exchange for cotton because there wasn't enough on the market. They wanted to design running singlets that were compostable. Within five years they had a network of their best designers really passionate about these design challenges. These are all tough, tough problems; the only way to solve them is to get people excited.

How can companies shift their focus away from quarterly earnings to take a longer view?

That's an issue that has come up periodically during the development of the Society for Organizational Learning network. Usually it comes from an elder, a retired CEO who says: "If I really look back, a big blind spot for all of us is that we take as given the primacy of the shareholder." When the limited liability corporation was created 140 years ago, this made sense.

The shareholder had to be protected. But it makes no sense any more. We live in a world that has a surplus of financial capital, and great shortages of natural capital, human capital, and, in some places, social capital. We're optimizing around one input!

How else does the corporation need to change?

You go to any MBA program, and you will be taught the theory of the firm, that the purpose of the firm is the maximization of return on invested capital. I always thought this was a kind of lunacy. A well-managed business will have a high return on invested capital. But that's a consequence. It's not a way to manage a business. I remember a great quote of Peter Drucker. He said: "Profit for a company is like oxygen for a person. If you don't have enough of it, you're out of the game. But if you think your life is about breathing, you're really missing something." The purpose [of an enterprise] is never making money. And I think a lot of the best innovators inside big companies, the reason they succeed is that they really understand the theory of their business.

Costco is about long-term, reliable, quality supply. It's the key to the business. When the woman who got the Food Lab work embedded in Costco first started talking about the predicament of farmers, people were a little suspicious. They thought the predicament of farmers is a big problem in the world. That's why there are charities, and that's why we give money to charities. They couldn't see the connection to their business until she got them to see that they wouldn't have long-term quality supply if farming communities were destroyed. So she connected the issue to the theory of their business—but not the economic theory of the firm. Well-managed businesses could not possibly have gotten where they are believing this [economic theory of the firm] nonsense.

Where are we in the adoption of the Necessary Revolution?

We're pretty much in the beginning. I can certainly say that from the 10 years since we organized this network, the people who joined were small bands of radicals in their companies, even if they were senior. But in virtually all of those companies, those people aren't radicals anymore. There are wild cards obviously: major economic decline. Innovation requires resources to invest, and you can see many companies pulling back and going into an intense protective mode in a major extended period of financial distress.

What role can governments play?

If you are realistic about how our present society works, the economic clout—and a lot of the political clout, frankly—is in the business sector. And it's the locus of innovation. But you've got to build these networks. I think Paul Hawken's recent book, Blessed Unrest: How the Largest Movement in the World Came into Being and Why No One Saw It Coming (Viking Press, 2007) was on the money. The growth of the civil society is historic, and in some ways it's a response to the inability of government to deal with these kind of issues. Governments, especially democratic ones, are short-term and nationalistic. These problems are long-term and global.

And businesses are inherently more global?

Yes, they're global, and because they're global they've begun to build partnerships across their value chains. But I don't think business is sufficient. We're going to see a lot of partnerships, as companies partner with global organizations like the World Wildlife Fund and Oxfam and, eventually, with governments.

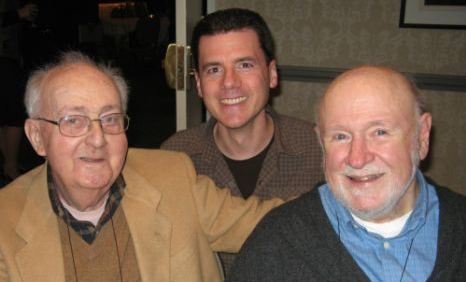

photo of (from right to left) Peter Scholtes, John Hunter and George Box in Madison, Wisconsin at the 2008 Deming Conference

photo of (from right to left) Peter Scholtes, John Hunter and George Box in Madison, Wisconsin at the 2008 Deming Conference