Photo by Gokhan Sahin/Getty Images

It’s a good time to be a pessimist. ISIS, Crimea, Donetsk, Gaza, Burma, Ebola, school shootings, campus rapes, wife-beating athletes, lethal cops—who can avoid the feeling that things fall apart, the center cannot hold? Last year Martin Dempsey, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, testified before a Senate committee that the world is “more dangerous than it has ever been.” This past fall,Michael Ignatieff wrote of “the tectonic plates of a world order that are being pushed apart by the volcanic upward pressure of violence and hatred.” Two months ago, the New York Times columnist Roger Cohen lamented, “Many people I talk to, and not only over dinner, have never previously felt so uneasy about the state of the world. … The search is on for someone to dispel foreboding and embody, again, the hope of the world.”

As troubling as the recent headlines have been, these lamentations need a second look. It’s hard to believe we are in greater danger today than we were during the two world wars, or during other perils such as the periodic nuclear confrontations during the Cold War, the numerous conflicts in Africa and Asia that each claimed millions of lives, or the eight-year war between Iran and Iraq that threatened to choke the flow of oil through the Persian Gulf and cripple the world’s economy.

How can we get a less hyperbolic assessment of the state of the world? Certainly not from daily journalism. News is about things that happen, not things that don’t happen. We never see a reporter saying to the camera, “Here we are, live from a country where a war has not broken out”—or a city that has not been bombed, or a school that has not been shot up. As long as violence has not vanished from the world, there will always be enough incidents to fill the evening news. And since the human mind estimates probability by the ease with which it can recall examples, newsreaders will always perceive that they live in dangerous times. All the more so when billions of smartphones turn a fifth of the world’s population into crime reporters and war correspondents.

We also have to avoid being fooled by randomness. Cohen laments the “annexations, beheadings, [and] pestilence” of the past year, but surely this collection of calamities is a mere coincidence. Entropy, pathogens, and human folly are a backdrop to life, and it is statistically certain that the lurking disasters will not space themselves evenly in time but will frequently overlap. To read significance into these clusters is to succumb to primitive thinking, a world of evil eyes and cosmic conspiracies.

Finally, we need to be mindful of orders of magnitude. Some categories of violence, like rampage shootings and terrorist attacks, are riveting dramas but (outside war zones) kill relatively small numbers of people. Every day ordinary homicides claim one and a half times as many Americans as the number who died in the Sandy Hook massacre. And as the political scientist John Mueller points out, in most years bee stings, deer collisions, ignition of nightwear, and other mundane accidents kill more Americans than terrorist attacks.

The only sound way to appraise the state of the world is to count. How many violent acts has the world seen compared with the number of opportunities? And is that number going up or down? As Bill Clinton likes to say, “Follow the trend lines, not the headlines.” We will see that the trend lines are more encouraging than a news junkie would guess.

To be sure, adding up corpses and comparing the tallies across different times and places can seem callous, as if it minimized the tragedy of the victims in less violent decades and regions. But a quantitative mindset is in fact the morally enlightened one. It treats every human life as having equal value, rather than privileging the people who are closest to us or most photogenic. And it holds out the hope that we might identify the causes of violence and thereby implement the measures that are most likely to reduce it. Let’s examine the major categories in turn.

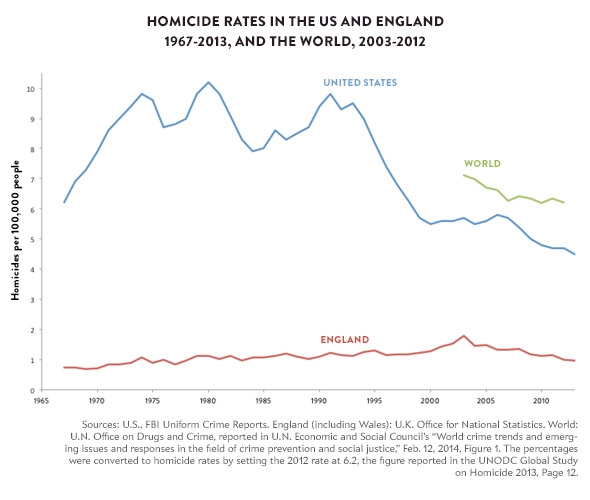

Homicide. Worldwide, about five to 10 times as many people die in police-blotter homicides as die in wars. And in most of the world, the rate of homicide has been sinking. The Great American Crime Decline of the 1990s, which flattened out at the start of the new century, resumed in 2006, and, defying the conventional wisdom that hard times lead to violence, proceeded right through the recession of 2008 and up to the present.

England, Canada, and most other industrialized countries have also seen their homicide rates fall in the past decade. Among the 88 countries with reliable data, 67 have seen a decline in the past 15 years. Though numbers for the entire world exist only for this millennium and include heroic guesstimates for countries that are data deserts, the trend appears to be downward, from 7.1 homicides per 100,000 people in 2003 to 6.2 in 2012.

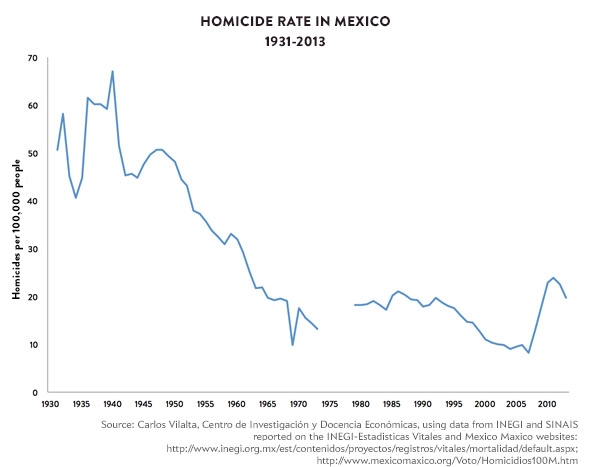

The global average, to be sure, conceals many regions with horrific rates of killing, particularly in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa. But even in those hot zones, it’s easy for the headlines to mislead. The gory drug-fueled killings in parts of Mexico, for example, can create an impression that the country has spiraled into Hobbesian lawlessness. But the trend line belies the impression in two ways.

One is that the 21st-century spike has not undone a massive reduction in homicide that Mexico has enjoyed since 1940, comparable to the reductions that Europe and the United States underwent in earlier centuries. The other is that what goes up often comes down. The rate of Mexican homicide has declined in each of the past two years (including an almost 90 percent drop in Juárez from 2010 to 2012), and many other notoriously dangerous regions have experienced significant turnarounds, including Bogotá, Colombia (a fivefold decline in two decades), Medellín, Colombia (down 85 percent in two decades), São Paolo (down 70 percent in a decade), the favelas of Rio de Janeiro (an almost two-thirds reduction in four years), Russia (down 46 percent in six years), and South Africa (a halving from 1995 to 2011). Many criminologists believe that a reduction of global violence by 50 percent in the next three decades is a feasible target for the next round of Millennium Development Goals.

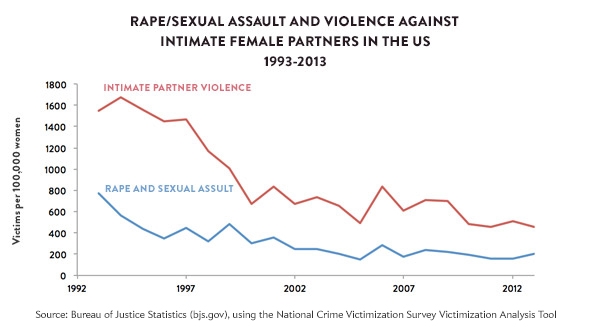

Violence Against Women. The intense media coverage of famous athletes who have assaulted their wives or girlfriends, and of episodes of rape on college campuses, have suggested to many pundits that we are undergoing a surge of violence against women. But the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics’ victimization surveys (which circumvent the problem of underreporting to the police) show the opposite: Rates of rape or sexual assault and of violence against intimate partners have been sinking for decades, and are now a quarter or less of their peaks in the past. Far too many of these horrendous crimes still take place, but we should be encouraged by the fact that a heightened concern about violence against women is not futile moralizing but has brought about measurable progress—and that continuing this concern can lead to greater progress still.

Few other countries have comparable data, but there is reason to believe that similar trends would be found elsewhere. Most measures of personal violence are correlated over time, so the global decline of homicide suggests that nonlethal violence against women may be falling on a parallel trajectory, though highly unevenly across regions. In 1993 the U.N. General Assembly adopted a Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women, and polling data show widespread support for women’s rights, even in countries with the most benighted practices. Many countries have implemented laws and public awareness campaigns to reduce rape, forced marriage, genital mutilation, honor killings, domestic violence, and wartime atrocities. Though some of these measures are toothless, and the effectiveness of others has yet to be established, there are grounds for optimism over the long term. Global shaming campaigns, even when they start out as purely aspirational, have led in the past to dramatic reductions of practices such as slavery, dueling, whaling, foot binding, piracy, privateering, chemical warfare, apartheid, and atmospheric nuclear testing.

Violence Against Children. A similar story can be told about children. The incessant media reports of school shootings, abductions, bullying, cyberbullying, sexting, date rape, and sexual and physical abuse make it seem as if children are living in increasingly perilous times. But the data say otherwise: Kids are undoubtedly safer than they were in the past. In a review of the literature on violence against children in the United States published earlier this year, the sociologist David Finkelhor and his colleagues reported, “Of 50 trends in exposure examined, there were 27 significant declines and no significant increases between 2003 and 2011. Declines were particularly large for assault victimization, bullying, and sexual victimization.”

Similar trends are seen in other industrialized countries, and international declarations have made the reduction of violence against children a global concern.

Democratization. In 1975, Daniel Patrick Moynihan lamented that “liberal democracy on the American model increasingly tends to the condition of monarchy in the 19thcentury: a holdover form of government, one which persists in isolated or peculiar places here and there … but which has simply no relevance to the future.” Moynihan was a social scientist, and his pessimism was backed by the numbers of his day: A growing majority of countries were led by communist, fascist, military, or strongman dictators. But the pessimism turned out to be premature, belied by a wave of democratization that began not long after the ink had dried on his eulogy. The pessimists of today who insist that the future belongs to the authoritarian capitalism of Russia and China show no such numeracy. Data from the Polity IV Project on the degree of democracy and autocracy among the world’s countries show that the democracy craze has decelerated of late but shows no signs of going into reverse.

Democracy has proved to be more robust than its eulogizers realize. A majority of the world’s countries today are democratic, and not just the wealthy monocultures of Europe, North America, and East Asia. Governments that are more democratic than not (scoring 6 or higher on the Polity IV Project’s scale from minus 10 to 10) are entrenched (albeit with nerve-wracking ups and downs) in most of Latin America, in floridly multiethnic India, in Islamic Turkey, Malaysia, and Indonesia, and in 14 countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Even the autocracies of Russia and China, which show few signs of liberalizing anytime soon, are incomparably less repressive than the regimes of Stalin, Brezhnev, and Mao.

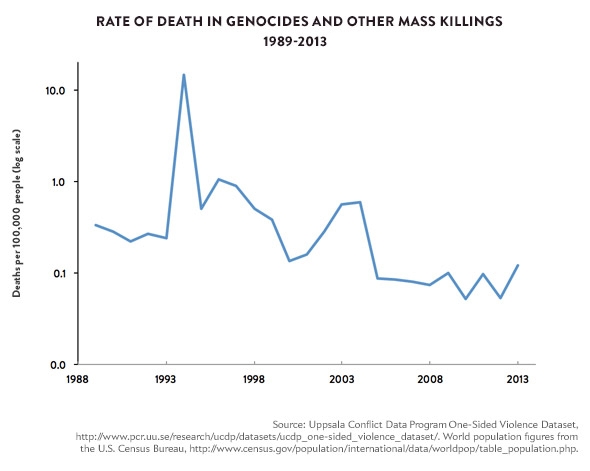

Genocide and Other Mass Killings of Civilians.The recent atrocities against non-Islamic minorities at the hands of ISIS, together with the ongoing killing of civilians in Syria, Iraq, and central Africa, have fed a narrative in which the world has learned nothing from the Holocaust and genocides continue unabated. But even the most horrific events of the present must be put into historical perspective, if only to identify and eliminate the forces that lead to mass killing. Though the meaning of the word genocide is too fuzzy to support objective analysis, all genocides fall into the more inclusive category of “one-sided violence” or “mass killing of noncombatant civilians,” and several historians and social scientists have estimated their trajectory over time. The numbers are imprecise and often contested, but the overall trends are clear and consistent across datasets.

By any standard, the world is nowhere near as genocidal as it was during its peak in the 1940s, when Nazi, Soviet, and Japanese mass murders, together with the targeting of civilians by all sides in World War II, resulted in a civilian death rate in the vicinity of 350 per 100,000 per year. Stalin and Mao kept the global rate between 75 and 150 through the early 1960s, and it has been falling ever since, though punctuated by spikes of dying in Biafra (1966–1970, 200,000 deaths), Sudan (1983–2002, 1 million), Afghanistan (1978–2002, 1 million), Indonesia (1965–1966, 500,000), Angola (1975–2002, 1 million), Rwanda (1994, 500,000), and Bosnia (1992–1995, 200,000). (All of these estimates are from the Center for Systemic Peace.) These numbers must be kept in mind when we read of the current horrors in Iraq (2003–2014, 150,000 deaths) and Syria (2011–2014, 150,000) and interpret them as signs of a dark new era. Nor, tragically, are the beheadings and crucifixions of the Islamic State historically unusual. Many postwar genocides were accompanied by splurges of ghastly torture and mutilation. The main difference is that they were not broadcasted on social media.

The trend lines for genocide and other civilian killings, fortunately, point sharply downward. After a steady rise during the Cold War until 1992, the proportion of states perpetrating or enabling mass killings of civilians has plummeted, though with a small recent bounce we will examine shortly.

The number of civilians killed in these massacres has also dropped. Reliable data, collected by the Uppsala Conflict Data Program, or UCDP, exist only for the past 25 years, and this period is so dominated by the Rwandan genocide that an ordinary graph looks like a tall spike poking through a wrinkled carpet. But when we squish the graph by using a logarithmic scale, we see that by 2013 the rate of civilian killing had fallen by an order of magnitude since the mid-1990s, and by two orders of magnitude since Rwanda.

Though comparisons to the cruder data of previous decades are iffy, the numbers we have suggest that the rate of killing civilians has dropped by about three orders of magnitude since the decade after World War II, and by four orders of magnitude since the war itself. In other words, the world’s civilians are several thousand times less likely to be targeted today than they were 70 years ago.

War. Researchers who track war and peace distinguish “armed conflicts,” which kill as few as 25 soldiers and civilians caught in the line of fire in a year, from “wars,” which kill more than a thousand. They also distinguish “interstate” conflicts, which pit the armed forces of two or more states against each other, from “intrastate” or “civil” conflicts, which pit a state against an insurgency or separatist force, sometimes with the armed intervention of an external state. (Conflicts in which the armed forces of a state are not directly involved, such as the one-sided violence perpetrated by a militia against noncombatants, and intercommunal violence between militias, are counted separately.)

In a historically unprecedented development, the number of interstate wars has plummeted since 1945, and the most destructive kind of war, in which great powers or developed states fight each other, has vanished altogether. (The last one was the Korean War). Today the world rarely sees a major naval battle, or masses of tanks and heavy artillery shelling each other across a battlefield. The green curve in the graph below (from the UCDP) shows how major wars have sputtered out in the postwar period.

The end of the Cold War also saw a steep reduction in the number of armed conflicts of all kinds, including civil wars. The blue curve in the graph shows that recent events have not reversed this trend. In 2013 there were 33 state-basedarmed conflicts in the world, a number that falls right within the range of fluctuations of the last dozen years (between 31 and 38) and well below the high of 52 shortly after the end of the Cold War. The UCDP has also noted that 2013 saw the signing of six peace agreements, two more than in the previous year.

But the red curve in the graph shows a recent development that is less benign: The number of wars jumped from four in 2010—the lowest total since the end of World War II—to seven in 2013. These wars were fought in Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iraq, Nigeria, Pakistan, South Sudan, and Syria. Conflict data for 2014 will not be available until next year, but we already know that four new wars broke out in the past 12 months, for a total of 11. The jump from 2010 to 2014, the steepest since the end of the Cold War, has brought us to the highest number of wars since 2000. The worldwide rate of battle deaths (available through 2013) has also risen since its low point in 2005, mostly because of the deaths in the Syrian civil war.

Though the recent increase in civil wars and battle deaths is real and worrisome, it must be kept in perspective. It has undone the progress of the last dozen years, but the rates of violence are still well below those of the 1990s, and nowhere near the levels of the 1940s, 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, or 1980s.

The 2010–2014 upsurge is circumscribed in a second way. In seven of the 11 wars that flared during this period, radical Islamist groups were one of the warring parties: Afghanistan, Pakistan, Israel/Gaza, Iraq, Nigeria, Syria, and Yemen. (Indeed, absent the Islamist conflicts, there would have been no increase in wars in the last few years, with just two in 2013 and three in 2014.) This reflects a broader trend. In January 2014 the Pew Research Center reported that the number of countries experiencing high or very high levels of “religious hostilities” increasedby more than 40 percent (from 14 to 20) between 2011 and 2012. In all but two of these countries (those listed above together with Bangladesh, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Lebanon, the Palestinian Territories, Russia, Somalia, Sudan, and Thailand) the hostilities were associated with extremist Islamist groups. These groups tend to gain the most traction in countries with exclusionary, inept, or repressive governments or in zones with no effective government at all, including long-anarchic frontier regions and the parts of Syria and Iraq that have been rendered anarchic in the aftermath of the invasion of Iraq and the Arab Spring.

Because the radical Islamist groups have maximalist goals and reject compromise, the major mechanisms that drove the decline in the number of wars in the preceding decades—negotiated settlements and peacekeeping and peacebuilding programs—are unlikely to succeed in ending these conflicts. Also intensifying the violence is their international scope. External fighters and weapons drive up death tolls and prolong fighting. For these reasons we do not expect the recent upsurge to be quickly reversed.

At the same time, there are reasons to believe that it will not extend into the indefinite future, let alone escalate into global warfare. Let’s examine the three most prominent trouble spots.

Iraq/Syria. The Islamic State will not expand into a pan-Islamic caliphate, and it is unlikely to persist over the long term. For one thing, its ideology and politics are loathed throughout most of the Islamic world; even al-Qaida has excommunicated the movement for being too extreme. The extremists thus lack the mass popular support that is necessary for fighting the kind of “people’s war” that proved successful in places like China and Vietnam.

The Islamic State, moreover, lacks the conventional military capabilities needed to overthrow a heavily defended Baghdad. It has minimal armor, long-range artillery, sophisticated rocketry, and air power, and only a rudimentary air defense system. The Islamists’ remarkable sweep through northern Iraq in the summer of 2014 occurred mainly because hapless Iraqi soldiers, abandoned by officers with no loyalty to the Shiite regime, chose not to fight.

The Islamic State is now overextended and will become more vulnerable as it seeks to become a normal state. Although wealthy by terror group standards, its income—estimated at $2 million a day—is grossly inadequate to the task of governing as a state. It is already under the same U.N. sanction regime as al-Qaida, and it is isolated from the region’s main centers of trade, manufacture, and commerce. As ISIS is decreasingly able to extract, refine, and sell oil, its major source of revenue is shrinking. It has no access to the sea, it has no major-power supporters, and its neighbors are mostly enemies. Last but not least, the United States and its allies, together with the Iraqi army, are planning a spring counteroffensive against ISIS that will be far more punishing than anything attempted thus far.

Ukraine. Vladimir Putin’s reabsorption of Crimea into Russia, and his thinly disguised support for Ukrainian secessionist movements, are deeply troubling developments, not just because the resulting fighting has claimed more than 4,000 lives, but also because they challenge the grandfathering of national borders and the near-taboo on conquest that have helped keep the peace since 1945.

Yet comparisons to the world of a century ago—when romantic militarism was widespread, international institutions virtually nonexistent, and leaders naive about the costs of escalating great-power war—are almost certainly overdrawn. So far Russia has sent “little green men” rather than tank divisions across the border, and even the most hawkish of American hawks has not proposed pushing it back with military force. Meanwhile Putin’s adventurism has been hugely costly for Russia. The tough EU sanctions, along with plunging oil prices, will push Russia into a recession in 2015. The ruble is plummeting in value, food prices have risen sharply, and Russian banks are finding it increasingly difficult to borrow foreign capital. All this suggests that the tensions in Ukraine are far more likely to end in an uneasy stalemate like those in Georgia and Moldova, which have endured the loss of pro-Russian breakaway statelets, than a repeat of World War I.

Israel and Palestine. The recurring outbursts of violence between Israel and the Palestinians, including the incursion into Gaza last summer that killed 2,000 people, have obscured two facts that come into view only from a historical and quantitative vantage point.

First, the Israel-Palestine conflict was once a far more dangerous Israel-Arabconflict. Over the course of 25 years, Israel fought the armies of Egypt, Syria, and Jordan five times, with more than 100,000 battle deaths, and in 1973 both Israel and the United States put their nuclear forces on high alert in response to the threat. For the past 41 years there have been no such wars, and neither Egypt nor any other Arab regime has shown an interest in starting one.

For all the world’s obsession with the Israel-Palestine conflict, it has been responsible for a small proportion of the total human cost of war: approximately 22,000 deaths over six decades, coming in at 96th place among the armed conflicts recorded by the Center for Systemic Peace since 1946, and at 14th place among ongoing conflicts. That does not mean that the violence is acceptable, only that it should not be a cause of fatalism or despair. Worse conflicts have come to an end, not least ones that have embroiled Israel itself, and a peaceful settlement to this conflict should not be dismissed as utopian.

* * *

The world is not falling apart. The kinds of violence to which most people are vulnerable—homicide, rape, battering, child abuse—have been in steady decline in most of the world. Autocracy is giving way to democracy. Wars between states—by far the most destructive of all conflicts—are all but obsolete. The increase in the number and deadliness of civil wars since 2010 is circumscribed, puny in comparison with the decline that preceded it, and unlikely to escalate.

We have been told of impending doom before: a Soviet invasion of Western Europe, a line of dominoes in Southeast Asia, revanchism in a reunified Germany, a rising sun in Japan, cities overrun by teenage superpredators, a coming anarchy that would fracture the major nation-states, and weekly 9/11-scale attacks that would pose an existential threat to civilization.

Why is the world always “more dangerous than it has ever been”—even as a greater and greater majority of humanity lives in peace and dies of old age?

Too much of our impression of the world comes from a misleading formula of journalistic narration. Reporters give lavish coverage to gun bursts, explosions, and viral videos, oblivious to how representative they are and apparently innocent of the fact that many were contrived as journalist bait. Then come sound bites from “experts” with vested interests in maximizing the impression of mayhem: generals, politicians, security officials, moral activists. The talking heads on cable news filibuster about the event, desperately hoping to avoid dead air. Newspaper columnists instruct their readers on what emotions to feel.

There is a better way to understand the world. Commentators can brush up their history—not by rummaging throughBartlett’s for a quote from Clausewitz, but by recounting the events of the recent past that put the events of the present in an intelligible context. And they could consult the analyses of quantitative datasets on violence that are now just a few clicks away.

An evidence-based mindset on the state of the world would bring many benefits. It would calibrate our national and international responses to the magnitude of the dangers that face us. It would limit the influence of terrorists, school shooters, decapitation cinematographers, and other violence impresarios. It might even dispel foreboding and embody, again, the hope of the world.