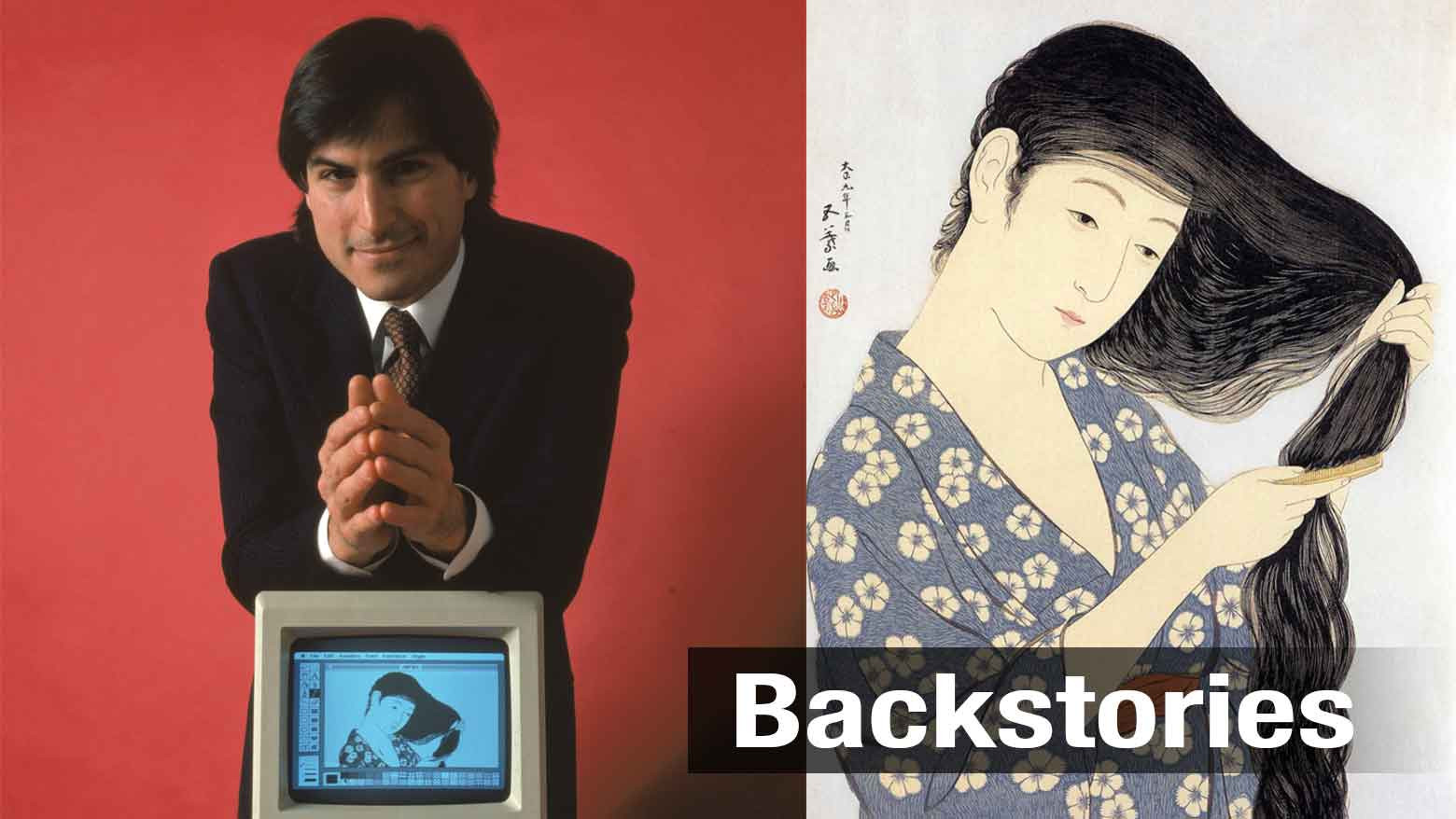

Backstories

The secret passion of Steve Jobs

新板畫運動

新版画

From Macintosh computers to iPhones, Steve Jobs was the architect of countless era-defining tech innovations. But the Apple founder was also known for his passion for Japanese culture. He often spoke about how he took inspiration from Zen Buddhism and his love of Japanese cuisine.

But there was another, lesser-known side to Jobs’ interest in Japanese culture. He was an ardent fan and collector of shin-hanga, or modern woodblock prints.

“A Woman on a Macintosh Screen”

When Jobs unveiled the first Macintosh computer to the media in January 1984, the screen displayed an image of a woodblock print: “A Woman Combing Her Hair”, by Hashiguchi Goyo.

Jobs bought two prints of the piece, in June 1983 and February 1984. It’s assumed he kept one for himself and the other for his company.

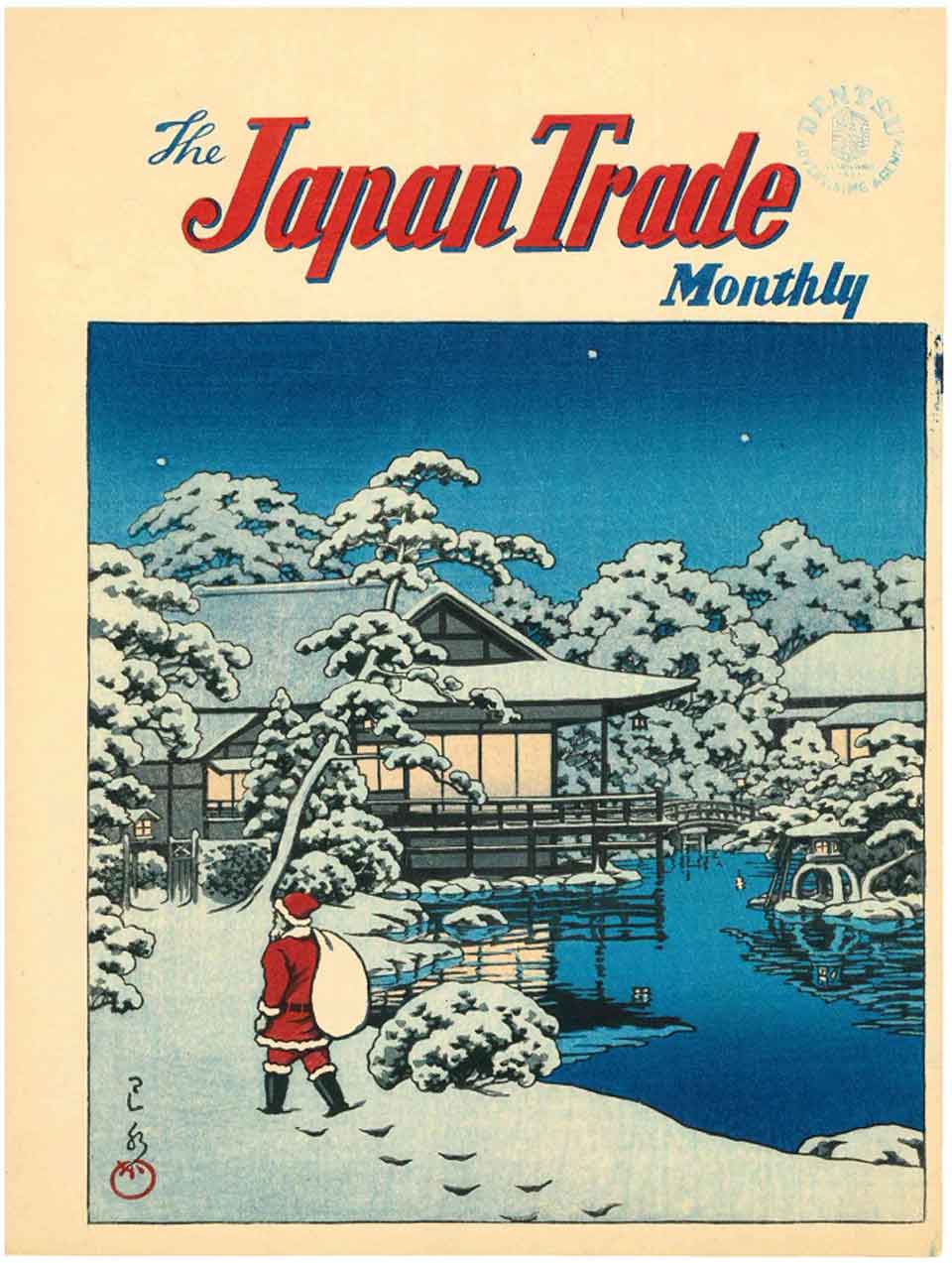

The work is an example of shin-hanga, woodblock prints produced in the early 20th century. They are characterized by their use of modern colors and mark a transition from the traditional ukiyo-e prints that were popular from the early 17th to late 19th century.

Shin-hanga were often used in posters and calendars to attract tourists to Japan. They were displayed at exhibitions in the US, which led to them being more popular abroad than in Japan. The peak of the shin-hanga movement was in the mid-1930s.

“Teach me about shin-hanga.”

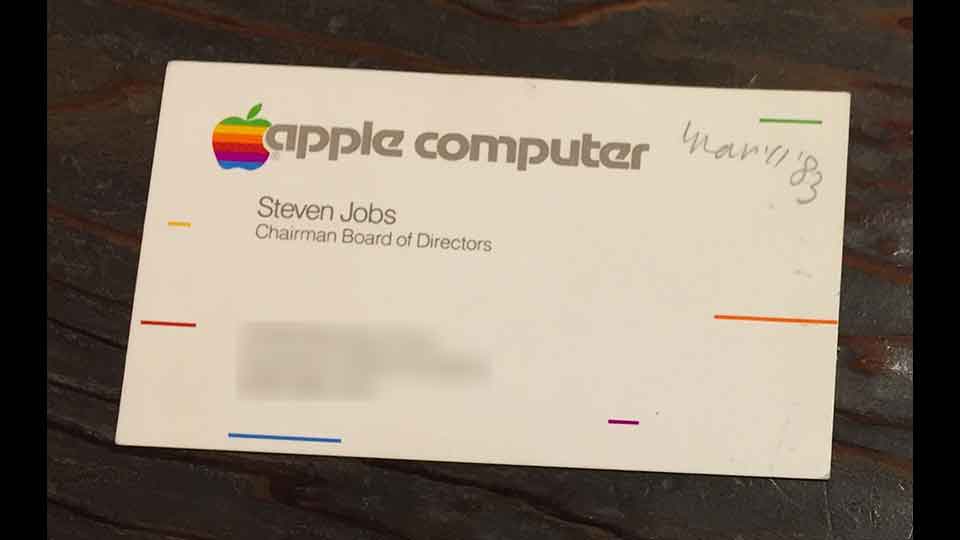

In March 1983, three young men visited a well-known gallery in Tokyo’s posh Ginza district. They wore jeans and t-shirts. One of them was Steve Jobs, the 28-year-old chairman of Apple. The other two were co-founder Steve Wozniak and Rod Holt, a colleague.

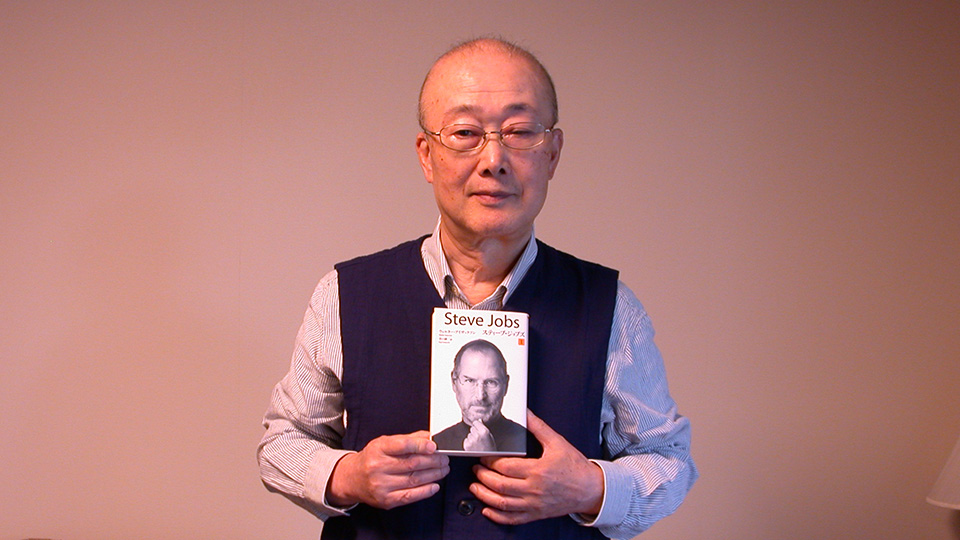

Matsuoka Haruo welcomed them in English. He had learned the language while working for the gallery’s San Francisco branch from 1969 to 1975.

“I had no idea who they were,” Matsuoka says. “But when I got home, I happened to see an article in the newspaper about Jobs. That’s when I realized who had been in the gallery.”

Matsuoka says he remembers being surprised by the business card Jobs gave him. It featured a colorful design, which was rare back then.

“He gave it to me and then asked me to teach him about shin-hanga,” Matsuoka says. “He wanted to collect.”

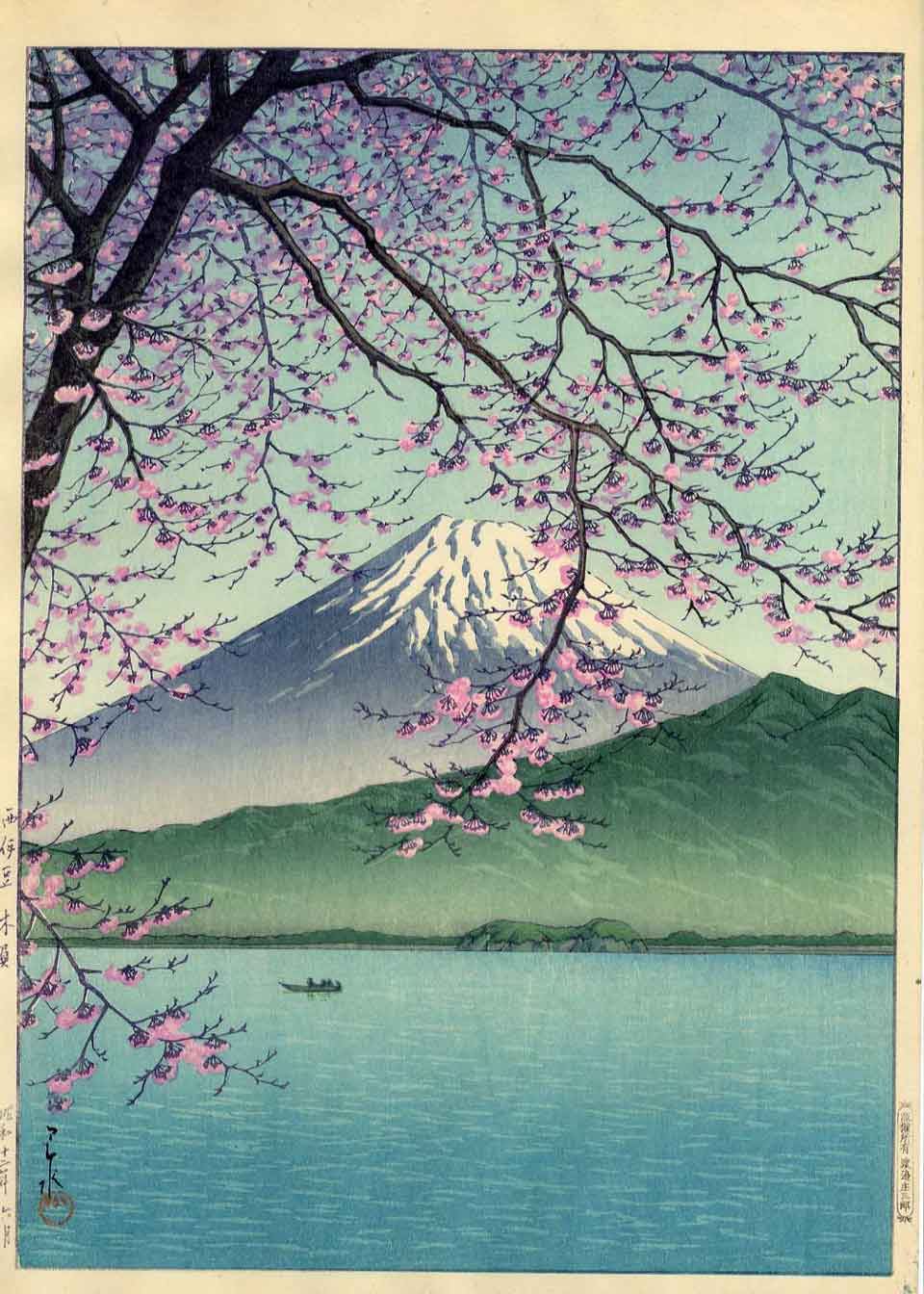

Jobs bought two shin-hanga prints during his first visit to the gallery. One depicted Mount Fuji and cherry blossoms, a theme that was popular among American and European collectors. But the second one was a rare—and expensive—portrait of a woman.

“I was impressed by the choice,” Matsuoka says.

This encounter in Ginza marked the beginning of a friendship that spanned two decades.

Impressive knowledge

Jobs often went to the gallery when he was in Japan, sometimes visiting twice a day. He preferred to go early and beat the crowds, and he once brought his daughter along.

“He asked me to teach him about shin-hanga but I quickly realized that he was very familiar with the style already,” Matsuoka says.

Matsuoka says when Jobs arrived at the gallery, he would show him prints in a backroom. Then Jobs would consult books showing various shin-hanga prints. It was a quick process and Matsuoka says it always seemed like Jobs knew precisely what he wanted.

“I was struck by his aesthetic sense,” Matsuoka says. “He knew which works were considered masterpieces. It seemed he had been studying shin-hanga for decades.”

Jobs was particularly keen on buying prints from before the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, which he knew were rare and valuable.

Matsuoka says Jobs bought at least 41 prints at the gallery, including 25 by Kawase Hasui, who was his favorite artist. He preferred portraits of women and pieces depicting snowy landscapes.

“He mostly chose prints that were peaceful and were rich in color,” Matsuoka says. “I think he may have felt a sense of nostalgia that was captured in these pieces.”

Business

The friendship between the two extended beyond art. Sometimes, Jobs would talk to Matsuoka about business.

Matsuoka says Jobs would tell him about his dealings with then-Sony chairman Morita Akio, about how Morita took him on a helicopter tour over Tokyo. He spoke about the negotiations over Apple’s use of Sony’s Trinitron tubes; Matsuoka remembers Jobs was as excited as a little boy when a deal was agreed.

When Jobs was ousted from Apple in 1985, Matsuoka remembers his friend as being angry and determined.

“He told me, ‘I’m keeping one share of the company and leaving’,” says Matsuoka.

“I think the woodblock prints provided him with an escape from the business world,” Matsuoka says. “They helped heal his emotional wounds and allowed him to take a break. I think they were very important to him.”

First encounters with shin-hanga.

Matsuoka will talk to customers about pieces at his gallery, but he makes it a point to never ask them about their preferences. And Jobs never told him where his interest in shin-hanga came from.

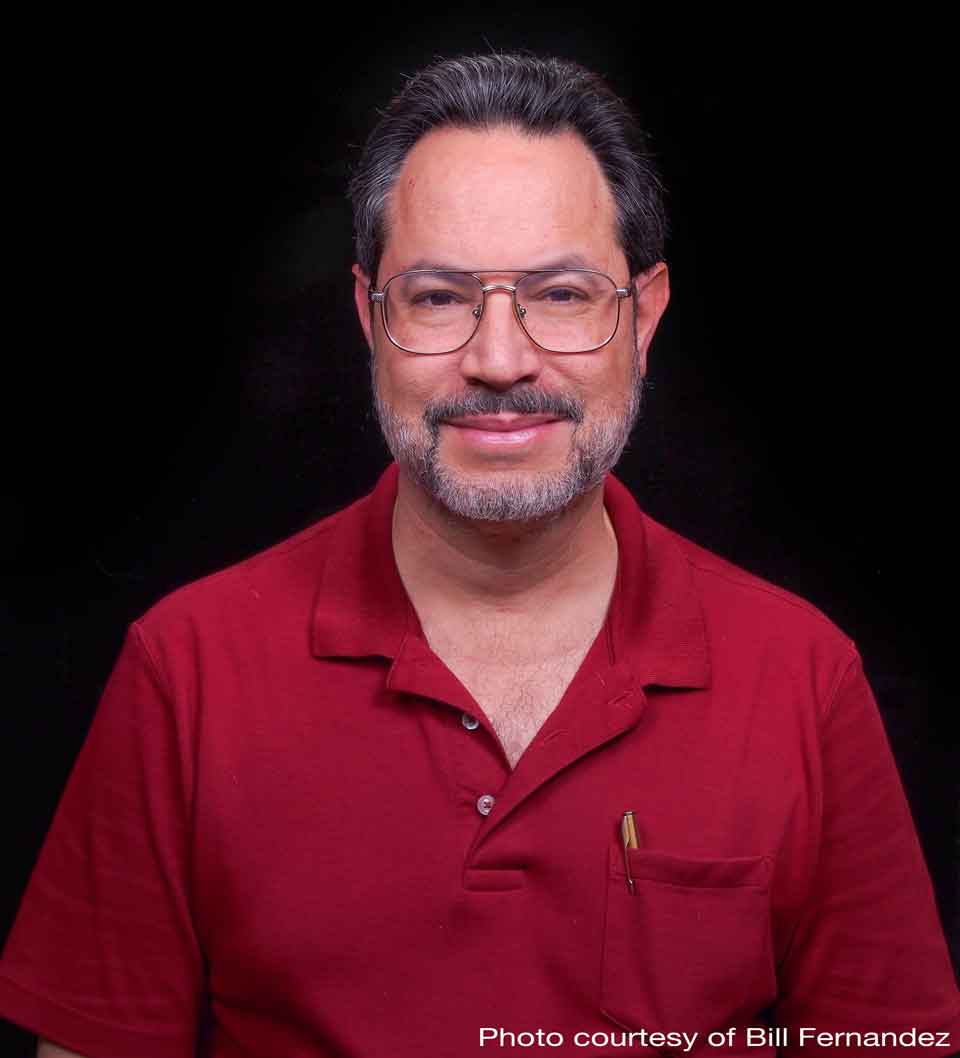

But Bill Fernandez, one of Jobs’ childhood friends and Apple’s first full-time employee, says he has an idea of what lay at the root of the fascination.

“My mother spurred his interest in woodblock prints.”

Fernandez’s grandfather had collected a number of prints by Kawase Hasui. His mother, who studied Japanese art at Stanford University, kept the pieces and hung them around the house. Jobs was captivated by them when he visited as a teenager. Kawase would end up becoming his favorite artist.

When Jobs visited the Ginza gallery years later, he was finally able to get his hands on a waterfall print by Kawase that he had seen so often at Fernandez’s house.

“He was definitely influenced by my mother,” Fernandez says. “I think the reason the print was on the screen during the Macintosh debut is because a graphic designer saw it at his house.”

Lifelong love

In 2011, 28 years after visiting the Ginza gallery, Jobs died of cancer. He was 56 years old.

The last time Matsuoka heard from him was in the fall of 2003. By this point, Matsuoka had left the Ginza gallery and set off on his own. One day, he received a message on the phone at his gallery.

“Hi Haru. I’m Steve Jobs.”

Years later, Matsuoka read a biography of his friend. He noticed a picture taken at Jobs’ home in 2004, which included a print hanging on a wall. It was one of the two pieces he had bought all those years ago, when he first visited the Ginza gallery.

“I knew from that picture that he remained an avid fan of shin-hanga until his death,” Matsuoka says. “It made me very happy to see that the print was so precious to him.”

“Jobs picked pieces based on his own sense, and most of them would turn out to be prominent works,” Matsuoka says. “If he had been able to continue, I think he would have built a great collection and played a crucial role in the world of shin-hanga. I wish we were able to see a complete Steve Jobs collection.”

Part of #Apple founder Steve Jobs' legacy is the refined artistic sensibilities he brought to product design. These ideas may have been influenced by a deep love for Japanese art. A Tokyo art dealer talks about their enduring friendship. #SteveJobs

沒有留言:

張貼留言